While there is a lot of concern about impending recession in the U.S., the traditional economic indicators of recession aren’t fully apparent, especially in the agricultural sector, according to Georgia’s State Fiscal Economist Jeffrey Dorfman, a professor of agricultural and applied economics in the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

“The interesting question is, if I run a business in agriculture, do I care about a recession? During a recession, we don’t cut back on food. Theoretically, we may cut back on restaurants, so if I were a grower who grew fancy vegetables for expensive restaurants or who raised specialized beef, I might be worried about a recession,” Dorfman said. “But, if I am growing peanuts, soybeans, blueberries, chickens or whatever else, I don’t think it matters.”

Yangxuan Liu, assistant professor of agricultural and applied economics at CAES, said that the agriculture industry — with the exception of the cotton industry — has traditionally acted as a buffer to the economy during recessionary periods.

Cotton plunges

“The majority of study about how agriculture responds to recession shows that the part of agriculture that contributes to the economy does not drop as much as the rest of the economy during recession, staying relatively stable. For Georgia agriculture, poultry, eggs and major row crops such as wheat and peanuts could navigate through this recession and provide some support for the state economy,” said Liu, who specializes in cotton economics.

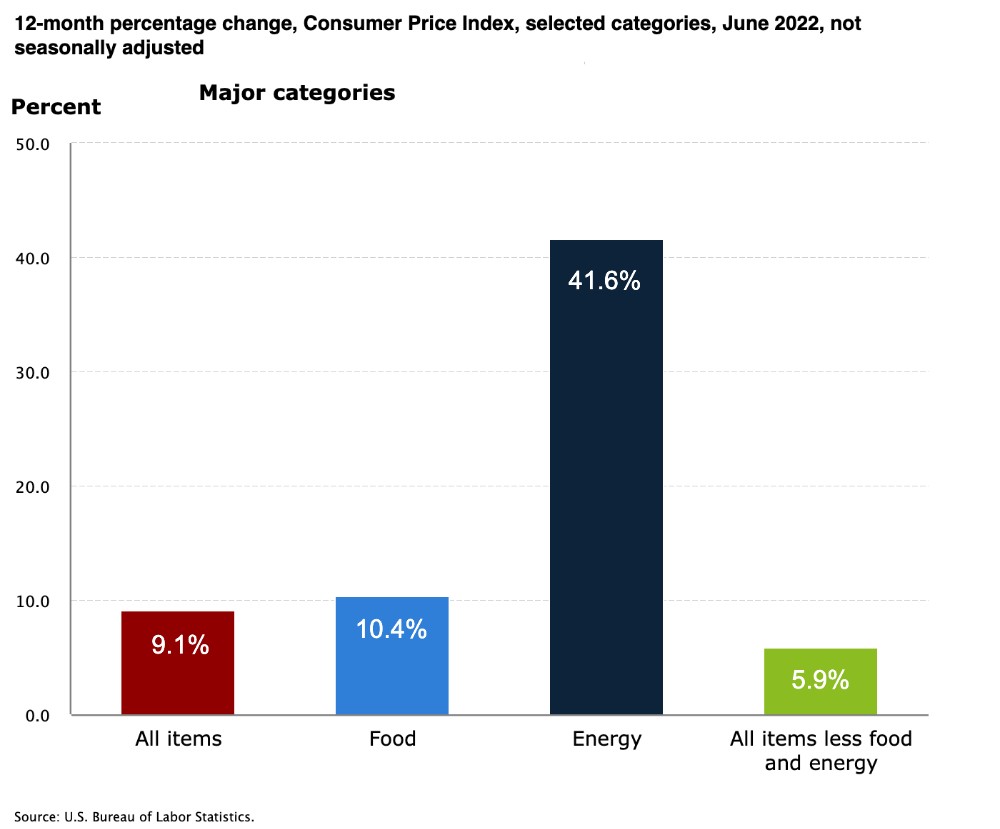

“Cotton and cotton-related products are discretionary items. Thus, cotton prices tend to follow the economy, with rising cotton prices during economic growth and declining cotton prices during recessions,” Liu wrote in a recent article for the Georgia Cotton Commission, explaining that soaring inflation has put extra pressure on consumers and impacted the cotton market. The annual inflation rate in the U.S. accelerated to 9.1% in June 2022, the highest since November 1981. Embedded in inflation, energy prices rose 41.6% and food costs surged 10.4%.

Extraordinary conditions

While a recession typically happens because the economy “got too excited somewhere,” the current factors disrupting the economy are not the same as those normally seen in a pre-recessionary period, Dorfman said.

“Whatever happens recession-wise, we need to understand that this is not a normal time. We have had an economy that was, in some sense, artificially good because the federal government gave out so much money in COVID relief and the economy artificially skewed toward stuff,” Dorfman explained. “Normally, people spend about 70% of their money on services — travel, entertainment, etc. — but during the pandemic we reduced the amount we spent on services, and we started spending all this extra money on stuff that we bought online.”

Now that spending patterns have primarily reverted toward services, businesses producing consumer goods are “feeling the pinch.”

“There may be bumps and economic growth may slow down, but if there is a recession, it will not be a normal one. The economy is not going to lose a lot of jobs,” Dorfman said.

Job security

Both during and after the COVID pandemic, the employment market has remained strong for job seekers.

“Normally one of the major characteristics of a recession is rising unemployment and the inability to get jobs,” Dorman said. “I am struggling to believe that a lot of businesses want to fire a lot of workers. They’ve just spent two years trying to desperately hire new workers and they are busy making projects to keep those workers busy for a while. If you used to work on an assembly line, they will keep paying you, but you’ll do other things for a while — because if the company fires people, they may never be able to hire replacements.”

For industries struggling to find enough workers to fill jobs, such as the retail and hospitality industries, Dorfman said they will have to get creative to find ways to make those jobs attractive.

“In agriculture, we are very familiar with this problem. For years it has been impossible to find anyone willing to do the jobs we need done. We need the guest worker program to bring in people willing to do these jobs. I could see the same thing happening in hospitality and retail eventually or they will have to find some way to reimagine those jobs,” he said.

While higher wages are a major factor, companies also can make jobs attractive to applicants with additional benefits beyond pay and health insurance, Dorfman said.

“Starbucks is an interesting example. They are halfway between retail and hospitality, and for several years they have offered tuition assistance because they know they can get workers that way. Other hospitality and retail employers can find similar ways to attract workers,” he said.

Capitalism and war

While economic indicators early in 2022 pointed toward economic recovery, Dorfman said there are many factors that have led to current fears of recession.

“The thing about capitalism and free enterprise is that there is no central coordination mechanism. For example, if Athens needs a new hotel, there is nothing stopping three different people from building a hotel. Now we have three hotels when we only needed one,” he explained. “If you have too much investment in anything — home building, auto manufacturing, growing cotton — the people in that industry start to lose money, and some go out of business. If that happens on a large enough scale, you have a recession.”

Similarly, because the world needs more wheat due to the global supply chain disruptions caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there is nothing in place to control how much wheat producers in other countries plant in response.

“What will happen six months from now when people finish harvesting corn and soybeans? Will they do a winter wheat crop? I assume that in places that traditionally grow wheat and had time to react, such as in the Northwest, that they planted every square inch they could find with wheat,” Dorfman said.

However, the wheat disruption has primarily affected prices and famine in Africa, where many countries import their wheat from Russia and Ukraine.

“The people who specialize in development economics and famine relief are in universal agreement that the answer is not to try to ship wheat to places like that, but to give them money to provide financial aid,” Dorfman said. “There is still enough wheat out there, but these places might need aid because it costs more.”

This is a press release from UGA. By Maria M. Lameiras